- 40 caregiver/child dyads will be enrolled.

- 6 community health workers will be trained.

Tiny smiles are making big changes in our families and communities.

-- Maribel Munoz, Principal Investigator

Proposal Title:

Community-based Family Coaching for Children with Developmental Risks in Lima, Peru

Country of Implementation:

Peru

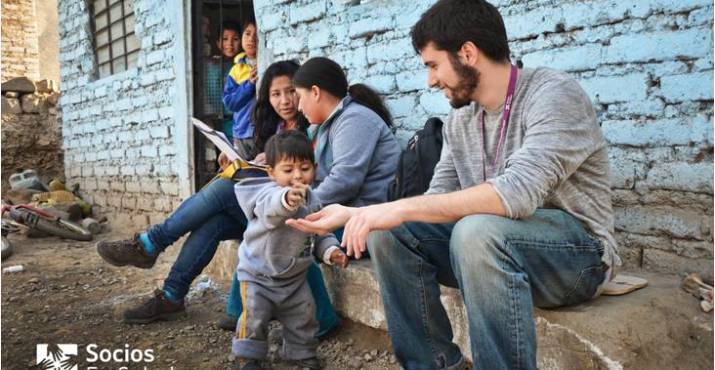

Organization:

Socios En Salud Sucursal Peru

Sites:

Carabayllo, Lima

Rural/Urban:

Rural & Urban

Target Beneficiary:

0-2 Years

Delivery Intermediaries:

Lady Healthcare Worker/Community Healthcare Worker; Caregiver

Objective:

Mitigate impact of neurodevelopmental delay on children’s brain development.

Innovation Description:

Standardized community-based screening and treatment program for children at risk of neurodevelopmental delays.

Stage of Innovation:

Proof of Concept

Proposal Title

Community-based Family Coaching for Children with Developmental Risks in Lima, Peru

Organization

Socios En Salud Sucursal Peru

Sites

Carabayllo, Lima

Rural/Urban

Rural & Urban

Target Beneficiary

0-2 Years

Delivery Intermediaries

Lady Healthcare Worker/Community Healthcare Worker; Caregiver

Objective

Mitigate impact of neurodevelopmental delay on children’s brain development.

Innovation Description

Standardized community-based screening and treatment program for children at risk of neurodevelopmental delays.

Stage of Innovation

Proof of Concept

Despite documented efficacy of early interventions to treat neurodevelopmental delay (NDDs), the challenge for low-resource settings is to find a way to feasibly and effectively deliver evidence-based interventions to the vast population in need. In settings of poverty and limited health infrastructure, scalable solutions are difficult since children at greatest risk for NDD are often the least likely to access healthcare and specialized care to treat NDDs is limited.

The goal of the innovation is to demonstrate feasibility and efficacy of a community-based intervention that seeks to reduce NDD among children in the context of poverty and limited health infrastructure.

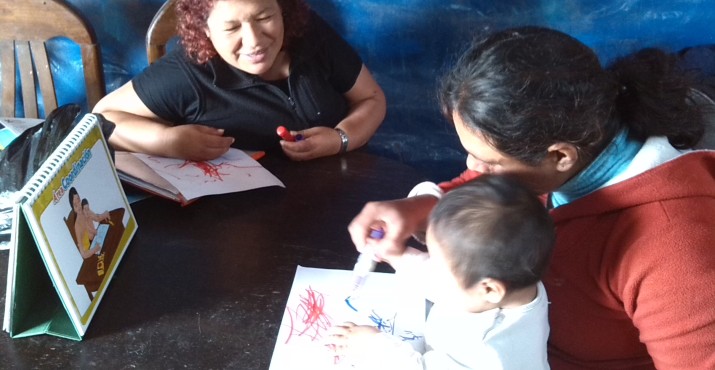

Community health workers will identify and treat children at-risk of NDDs and assist their caregivers. The intervention includes 1) coaching parents on how to stimulate their child to promote development, and 2) providing parents with social support and encouragement.

The children and their primary caregivers will be randomly assigned to one of three interventions: monthly nutritional support alone; nutritional support plus 3 months of the intervention in the home; or nutritional support plus 3 months of the intervention in group settings.

Tiny smiles are making big changes in our families and communities.

-- Maribel Munoz, Principal Investigator

Parents in the intervention group will be exposed to the community-based intervention (CBI) in 12 weekly sessions over 3 months, either at home or in a group setting at Socios En Salud in Carabayllo. The CBI is currently designed for one-on-one delivery, but will be adapted for group delivery and CHWs will be trained in group leadership and group CBI delivery.

The CBI framework has two elements:

1) Coaching parents on stimulation of their child’s development.

2) Providing parents with social support and encouragement.

Encounters between CHWs and caregivers are structured in four sequential steps: 1) Child observation & knowledge sharing about general child development; 2) Demonstration and initiation of reciprocal attention focusing and social interaction activities tailored to the child’s development; 3) Parent encouragement on parenting behavior and developmental interactions; 4) Parent social support through referral assistance, reassurance, and validation of parent concerns.

Children ages 6-24 months will be screened as per routine care at participating health centers, using the developmental screening instrument endorsed by the Peruvian Ministry of Health (Escala de Evaluacion del Desarollo Psychomotor, EEDP). To reach children who do not attend health centers, CHWs will also screen children in households using the same instrument. Children who screen positive for NDD risk and their primary caregiver will be invited to participate in the study. 40 dyads (children with NDD risk and their caregivers) will be enrolled and randomized to one of 3 arms: monthly food basket (control); monthly food basket plus individual CBI (home-based intervention); or monthly food basket plus group CBI (group intervention). We will follow participants for 6 months.

This study aims to answer the following questions: who benefits most from the intervention, child or caregiver? What is the extent of the benefit? How should the intervention be delivered for maximum effect (i.e. in a group vs. individual setting)? What are the essential elements to make the project sustainable at scale?

Funders

Key Partners

Key Drivers

Multi-sector Partnership

Socios En Salud Sucursal Peru engages with the Peruvian Ministry of Health as well as civil, social, and community-based organizations to ensure projects are sustainable at the community and municipal level.

Mutual Health Priority Amongst Invested Partners

Recent trends in Latin America toward decentralization of health services have shifted resources and leadership from Ministry of Health programs to local municipalities. Municipalities, such as Carabayllo, have resources and infrastructure to implement health programs, yet lack necessary expertise to execute programs effectively. Responding to this mandate, Rafael Alvarez Espinoza, Mayor of Carabayllo, identified the impact of child labor and social inequality on NDDs. As a result, he requested our organization to lend our expertise in community-based interventions to improving early neurodevelopment through a scalable, relatively low-cost program. Thus, this program represents a mutual health priority among invested partners and the collective resources necessary to leverage pilot findings towards in meaningful programmatic implementation.

Policy leaders, clinicians, and CHWs in Pisco/ Chincha and Carabayllo, Peru and similar stakeholders from two sister organizations (in Rwanda and Haiti) will be interviewed to explore how the intervention can be adapted to the different cultures, health systems, and socioeconomic characteristics of these diverse sites. The results will inform future development of a “core CBI package” with clear guidelines on adaptations for local populations.

Among the outcomes to be measured and evaluated:

The project will compare the change in developmental status among children and the change parenting behavior among caregivers across the control and intervention groups. Once enrolled, CHWs will administer the HOME questionnaire to evaluate parenting and home influences on child development, and they will conduct a brief assessment of the child’s birth history, health and nutritional status (clinical and psychosocial data). Videotapes of parent-child interactions will be taken at baseline, 3, and 6 months, and reviewed using standardized assessments adapted for Peru. The project team will compare changes in home influences, parent responsiveness, parental involvement, cognitive stimulation, and parent-child interactions (number & quality) across the control and intervention groups. Data will be collected at baseline, at 3 months into the intervention, and at 3 months post-intervention. The team will perform subgroup analyses to assess for heterogeneity of treatment effects due to caregiver, home, and child characteristics.

To assess the role of the delivery setting, the project will compare outcomes of each modality (group and individual lessons) in addition to qualitative data to compare the potential assets and limitations of each.

Process evaluations will include verbal caregiver surveys after each session and final focus groups for stakeholders, to improve the intervention through lessons learned.

To identify which aspects of the intervention are essential for scale and sustainability, the project team will interview policy leaders, clinicians, and CHWs in Peru, Rwanda and Haiti to explore how the intervention can be adapted to the contexts of these diverse sites.

Extended Ages and Stages Questionnaire (EASQ). Physical (Fine/Gross motor), cognitive, language, psychoemotional (adapted from Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ): Fernald, et al, Socioeconomic gradients in child development in very young children: Evidence from India, Indonesia, Peru and Senegal. PNAS. 109:2. October 16, 2012.

HOME Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Quantity and quality of child care experiences, quality of parent/child interactions/ relationships, home, social and arterial resources, family well-being and stress (Caregiver mental health, chaos, instability), parent involvement, parent responsivity, cognitive stimulation, quality of parent-child interactions.

Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)

Progress out of poverty index

Household food insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)

Hopkins Symptom Checklist (depression scale)

Global Stress Scale

Duke UNC Social Support Questionnaire

Conflicts Tactics Scale & Controlling behavior